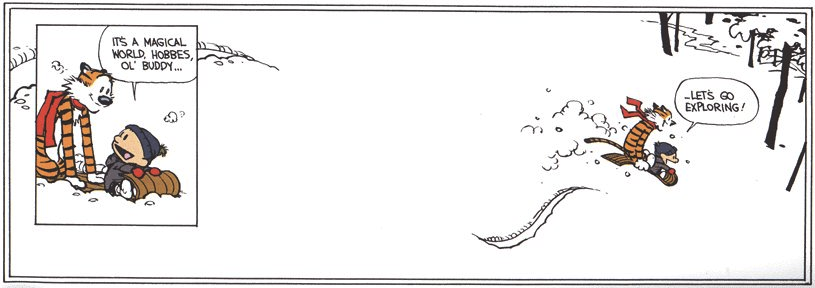

The flying arrow of time and the cyclical motion of the universe signal a year’s end for a pale blue dot flung into an obscure corner of the universe. Yet, the countless dreams, anxieties, hopes, fears and love emanating from its resident creatures fill the universe many times over. Reading books, for me, has always been about partaking in the multitude of thoughts animating our world and beyond; like dipping a finger in a gushing river to feel the cold current moving through one’s body. Here are some books that etched their mark on my mindscape in 2023:

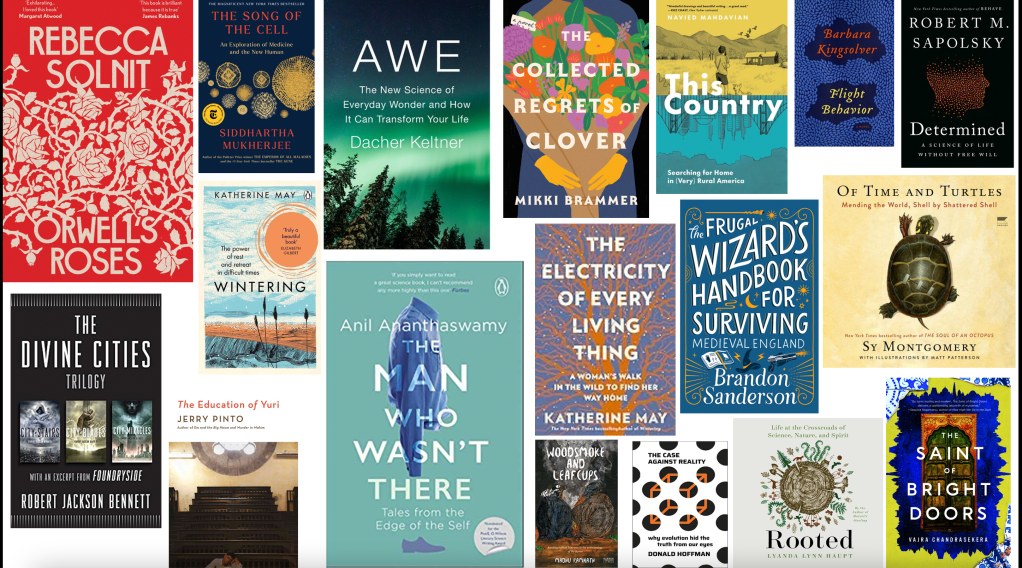

Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit (Non-Fiction)

The act of meandering isn’t appreciated enough, given the arbitrary linearity of thought, action and productivity embedded in the factory settings of society. In fact, meanderers are often seen as troublesome ‘deviants’, straying away from the existing path (never mind the warning signs along the way!). Yet, most things worth attending to, are to be found along the unmade paths, where trails of more-than-human point to unbounded possibilities. Solnit reclaims this wilderness through the political act of meandering through actions and evocative words. I loved her previous books and picked this one just to follow her words into yet another terrain enmeshing history, war and industrialization through the tender relationship of George Orwell with his garden. The writings ramble at a few places, but those are also enjoyable and reflective excursions. Here are some lines I picked, like wildflowers in an overgrown garden:

“Those obsessed with productivity and injustice often disparage doing nothing, though by doing nothing we usually mean a lot of subtle actions and observations and cultivation of relationships that are doing many kinds of something. It’s doing something whose value and results are not easily quantified or commodified, and you could argue that any of every evasion of quantifiability and commodifiability is a victory against assembly lines, authorities, and oversimplifications.”

Song of the cell by Siddhartha Mukherjee (Non-Fiction)

I don’t know why undergraduate and K-12 classes don’t include writings from authors like Siddhartha Mukherjee and Atul Gawande. These are authors I wish I had encountered earlier when I was a student, for the sheer wonder and inspiration they impart through their words, in addition to explaining dense concepts in a lucid fashion. Song of the cell traces the works of seminal scientists, their discoveries, failures and how every bit of knowledge, down to the level of sub-cellular functions reveals and deepens the mystery of human life simultaneously. Some book-marked quotes:

“‘The secret of learning is the systematic elimination of excess. We grow, mostly, by dying.’ We are hardwired not to be hardwired, and this anatomical plasticity may be the key to the plasticity of our minds.”

“It is one of the philosophical enigmas of immunity that the self exists largely in the negative – as holes in the recognition of the foreign. The self is defined, in part, by what is forbidden to attack it. Biologically speaking, the self is demarcated not by what is asserted but by what is invisible: It is what the immune system cannot see. “Tat Twam Asi”. “That [is] what you are.””

Lockwood and Co. by Jonathan Stroud (Vol 3,4,5) (YA fiction)

I ended up binge-reading these volumes on a weekend soon after watching the TV series based on the first two volumes. What’s not to love about teenage ghost-hunters and a wickedly clever commentary on power and class packed into a thrilling suspense?

Awe by Dacher Keltner (Non Fiction)

As someone who has long felt the moral need for experiences that can foreground the sheerness of the experiences itself; a momentary quietening of the mind’s desperate need to interpret, categorise and judge, this book literally spoke to my mind (with more than two decades of research to support specific arguments). Keltner traces the events that can give rise to awe across diverse contexts while explaining how such a transcendent emotion can be systematically studied and understood without lessening the sanctity of such experiences. If anything, the ability to feel awe can be consciously nurtured and enjoyed, as untethered oneness and an antidote to reductive categorization of perceptions.

The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer (Fiction)

I picked this book from the library display section, and getting to know authors this way has become my favourite mode of ‘surprise me’. Clover, who saw her kindergarten teacher drop dead when she was five, and lost her parents when they were vacationing in China at the age of six, is no stranger to death. Raised by her maternal grandfather in NYC, who has also died since, she becomes a death doula, shepherding the passing away of people, and making notes of their final moments into categories of ‘Regrets’, ‘Advice’ and ‘Confessions’. Lonely, yet resistant to change, she is thrown into it inevitably to confront herself with difficult questions about her own collected regrets. A compassionate, warm story like the perfect ramen bowl you didn’t know you needed.

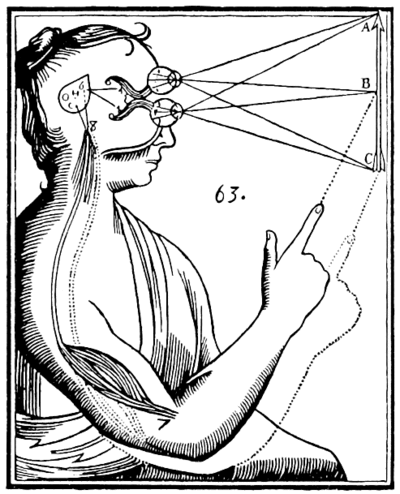

The man who wasn’t there by Anil Ananthaswamy

I have forever been fascinated by the big question in consciousness studies. Where does it come from? At what point do chemical and biological signalling between neurons give rise to the notion of ‘self’? Where do pathways of bodily electrical currents transmute into metanarratives of awareness? Through fascinating narratives of medical case studies ranging from schizophrenia, epilepsy, autism, Cotard’s syndrome and out-of-body experiences amongst others, Ananthaswamy explores the fragile connections holding together a sense of ‘I’, and how those threads can unravel to reveal fractals of awareness.

Divine cities Trilogy by Robert Jackson Bennet

I began reading it at my brother’s recommendation and devoured the volumes like a proper glutton. Fantasy novels doubling up as a thriller are irresistible to say the least; A clever social commentary weaved into the story makes for extra intrigue. Just read it already!

The Education of Yuri by Jerry Pinto

Pinto has the gift of weaving stories as if you were always a part of it. Reading him isn’t as much discovery as it is affirmation of one’s innermost feelings that are then not so secret after all. The honest, gut-wrenching relatability of characters draws you into their world effortlessly. This book spans the coming-of-age of Yuri Fonseca in 1980s Bombay where he explores friendship, sexual intimacy, bumps into Naxalism, is swept by grief, and still find some ground to walk on. That’s life, and we can never tire of it. Witty, compassionate and reflective, the books is filled with bumper sticker gems.

‘Wintering’, ‘Enchantment’ and the ‘The electricity of every living being’ by Katherine May

As you can see, I went on a trip with May and read all these books in quick succession. Reading her is a process of healing, without compromising on the need to engage with difficult aspects of one’s life and environment that seem so tempting to ignore. I’ll just mention a few quotes to illustrate the range of ideas discussed in the books.

“Doing those deeply unfashionable things – slowing down, letting your spare time expand, getting enough sleep, resting – is a radical act now, but it is essential. This is a crossroads we all know, a moment when you need to shed a skin. If you do, you’ll expose all those painful nerve endings and feel so raw that you’ll need to take care of yourself for a while. If you don’t then that skin will harden around you.” -Wintering

“Birds – ordinary birds – give the world its full three dimensions. Without them, the air is a flat surface, an absence of matter. Birds populate that space, explore it. They fill it with song. They mark the dawn and the dusk for us, the first heat of spring and the last gasp of autumn. In return, we are busy forgetting them.” – The electricity of every living being

“The deliberate pursuit of attention, ritual, or reflection does not mystically draw in anything external to me. Instead, it creates experiences that rearrange what I know to find the insights I need today. This is how symbolic thought works. It offers you a repository of understanding that can be triggered by the everyday, and which comes in a format that goes straight to the bloodstream. I don’t have the words to describe what it meant to play with my moon shadow. Instead, I feel it in my body, a kind of physical wonder at what is there waiting for me when I stop to notice.” – Enchantment

This Country: Searching for home in (very) rural America by Navied Mahdavian

This was a heart-warming, compassionate take on the struggles of moving from a city to a rural place, where romantic ideas of idyllic rural life soon turn into grinding hard work and uncomfortable cultural differences. Without dehumanizing or vilifying the ‘other’, Mahdavian skillfully conveys the sense of displacement, alienation and homecoming, all wrapped into the complexities of moving into a conservative place in the US Midwest.

Woodsmoke and Leafcups by Madhu Ramnath (Non-Fiction)

Informative and reflective, this book is a first-hand account of Ramnath’s life in Bastar, where he spent more than three decades. What began as an impulsive act of a rebellious youth slowly turned into a lifelong commitment and passion towards the land and its people. Written in the form of journal notes, the book traces fascinating accounts of the community, rituals, cultures and tensions with the state machinery.

The case against reality by Donald Hoffman (Non-Fiction)

A mind-boggling and deeply unsettling book, if one were to follow the implications, Hoffman systematically builds on the argument that we can never perceive ‘objective’ reality, and instead rely on interpretations that maximize our survival in the environment, following the fitness and adaptation trajectories in evolutionary theory. A recent conversation between Hoffman and Swami Sarvapriyananda delves into the implications of the ‘consciousness-first’ view (as opposed to the materialistic explanations of the evolution of consciousness)

Rooted by Landa Lynn Haupt (Non-Fiction)

Some writings are gentle affirmations of our unspoken thoughts. Rooted was like that for me. To have someone describe eloquently, something that you have always felt intuitively, is a true pleasure. More power to extended kinship and kithship based on reciprocity and love for the world we live in.

Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kingsolver (Fiction)

Set in a rural, Bible belt of America, the story opens with Dellarobia, an unhappy wife and a young mother of two, determinedly walking uphill to commence an affair; If life is going to hell, might as well sneak in some forbidden pleasure, she reasons. However, she finds her plans take an unexpected turn when her eyes land on what seems like a river of fire in the forest. She realizes she is surrounded by thousands of Monarch butterflies. The ensuing events offer a piercing commentary on how climate change is perceived by different communities, and the context in which specific issues are interpreted. Initially hailed as a miracle, then an inconvenience, and then a dire warning, the fate of the butterflies informs Dellarobia’s changing perception of the world, and what it would mean for her children. Searing, sensitive and poignant, Kingsolver weaves worlds with her writing. I look forward to reading more works by her this year.

Determined by Robert Sapolsky (Non-Fiction)

Sapolsky is one of my favourite non-fiction writers, since I read ‘A Primate’s Memoir’ by him. I wrote about this book in some detail in an earlier blog. Basically, a 600-page neuroscience-backed argument against free will, with a passionate call to let this realization make us more compassionate towards ourselves and each other.

Of Time and Turtles by Sy Montogomery (Non-Fiction)

Sy is another favourite author of mine. I love her writing style, and ways in which she can get readers deeply invested in the fate of the protagonists of her books (turtles and people who have been rescuing them in this case). Describing the emotionally-fraught and difficult task of caring, Sy pulls readers into the world of turtles and people refusing to give up on them despite shocking injuries. Reflecting on the resilience of turtles, despite the massive odds against them, she writes, “These babies are brave because they are wise, imbued with a wisdom that stretch back hundreds of millenia. That’s where wisdom orginated – not in some creed that humans made up. For true bravery and wisdom, we have to go back to turtle-knowing, the ancient wellspring that we too, can draw upon as we struggle to live bravely on the earth.”

The Frugal Wizard’s Handbook to Surviving Medieval England by Brandon Sanderson (Fiction)

I picked this book from the library display, thanks to its bright blue cover illustrations and curious title. I would have thought this to be something written by Terry Pratchett if the author wasn’t mentioned. It’s that much fun. A man waking up in what seems to be Medieval England, with fuzzy memories, scraps of a burnt guidebook titled The Frugal Wizard’s Handbook for Surviving Medieval England, and a bunch of thugs after him is a pretty action-packed premise. The pace never drops, and I finished it in one go like a brisk jog. Will this count for cardio?

The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekhara (Fiction)

This was a genre-defying book for me. From a baffling premise, to dream-like descriptions of places juxtaposed with group therapy and junk emails, the story is hard to pin down, much like the protagonist, Fetter. It felt like a book not as much concerned with the plot as it is with the mood. Rich descriptions of saints, mortals, anti-gods, political machinations and revolutionary uprisings could easily slip into incoherent prose, but Vajra skillfully weaves threads to lure readers deeper into the web of narratives until you seem to be sharing the conflicts of Fetter, with no comforting end in sight. Yet, there are ways to make peace and bask in the climax of revelations that come in the end.

As a writer, I draw endless inspiration from authors, and hope to gather enough thoughts to fill a book someday. Until then, I look forward to encountering more authors this year and picking nuggets of wisdom from their work. Feel free to comment on this post with any book that gave you company in the past year! I’d love to add it to my reading list if it’s new to me :).